• Environmental and explosives controls impact output, prices increase

• Magnesite supply reform: state control of raw magnesite sales

• Bauxite/BFA supply also challenged

How green is my valley? Mining of magnesite and production of magnesia in Liaoning province has been severely hit by a combination of very limited provision of explosives for mining and environmental inspections leading to plant closures. Chimney tops of CCM shaft kilns just visible in middle distance, while in far distance are ranges of exploited hillside deposits of magnesite.

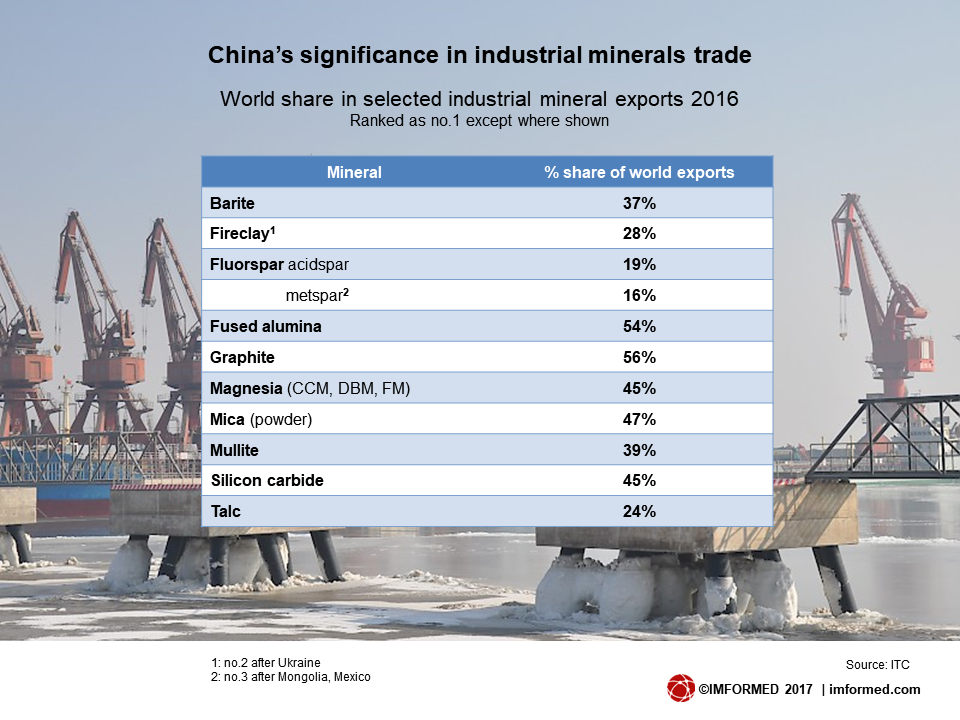

Just when traders thought they could breath a sigh of relief as China waved goodbye to export quotas on 1 January 2017, along comes a double whammy set to impact supplies of magnesia, bauxite, brown fused alumina, fluorspar and other minerals for the rest of the year and likely into 2018.

As IMFORMED reported in May 2017, robust government anti-pollution measures reaching out across the country’s mining industry had prompted the closure of many magnesia calcination and fusion plants in Liaoning province, China’s centre of magnesia output (see Magnesia maelstrom in China: Newsfile Report 31 May 2017).

This led to a squeeze on material availability and concern over the future of China’s production capacity situation for not only magnesia supply, but that of bauxite and brown fused alumina (BFA).

By early June a few operations had returned to production after having met environmental protection measures.

However, it now seems that the supply situation has hit a critical point in shortages, and for magnesia new reforms involving state control of supply hinted at during IMFORMED’s MagForum 2017 conference in Krakow may now come to pass.

Compounding the issue of plant closures due to environmental inspections has also been the government’s strict control over allocation of explosives for mine blasting, ie. a significant lack of dynamite has seriously curtailed magnesite ore extraction and thus feedstock to caustic calcined (CCM), dead burned (DBM), and fused magnesia (FM) plants.

Find out what’s really going on in China

China Refractory & Abrasive Minerals Forum 2018

10-12 September 2018, Shanghai

EARLY BIRD RATES | BOOK NOW!

Government mission to combat pollution

The catalyst for China’s zealous anti-pollution move was late last year on 12 December 2016, when China’s State Council released a national plan on environmental improvements for the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020), detailing tasks to clean up polluted air, water and soil.

The plan sets out objectives for a more environmentally friendly way of living, considerable reductions in major pollutants, effective control of environmental risks, and a sounder ecological system by 2020. Also included are eight obligatory environmental quality targets in the five-year plan for the first time.

As soon as festivities for the 2017 Chinese New Year concluded, on 1 February, the Liaoning provincial government started to carry out initial, but not too strict, environmental checks on industrial facilities.

On 5 April 2017, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) announced what was claimed as the largest national-level inspection on record, with more than 25 cities in north China facing a strict one-year inspection over air pollution prevention.

Some 5,600 environmental inspectors were sent to Beijing, Tianjin, and 26 smaller cities in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and nearby areas to check on implementation of pollution control targets and emission standards.

Duties included inspecting the investigation and closure of polluting businesses, the seasonal reduction or halting of production in certain industries, and the installation and operation of pollution monitoring and control devices.

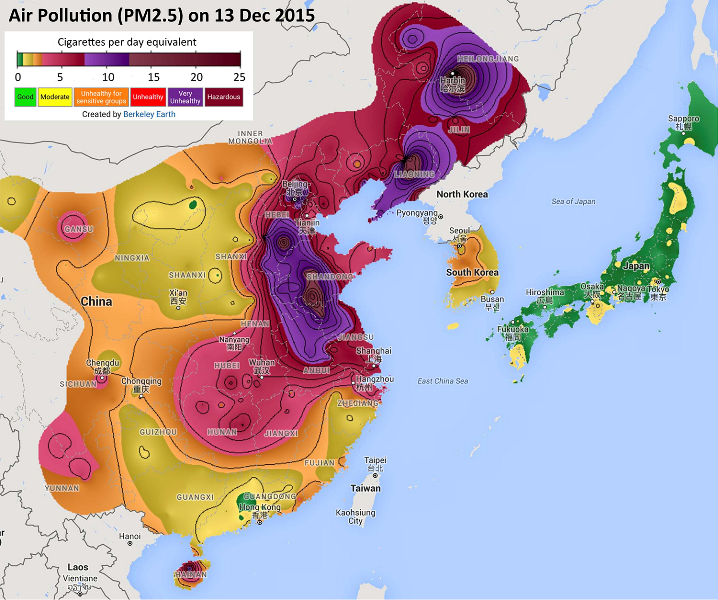

Cloud cover: air pollution measured in eastern China clearly reflecting the concentration of industrial facilities including mineral operations with Beijing and Tianjin municipalities (mineral processing for export), and Hebei, Henan, (bauxite, BFA), and Liaoning (magnesia) provinces suffering the worst pollution. On 5 April 2017, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) announced what was claimed as the largest national-level inspection on record, with more than 25 cities in north China facing a strict one-year inspection over air pollution prevention.

In Liaoning, inspections were intensified from 25 April with the central government sending in an eight-man environmental inspection team. This led to almost every CCM/DBM/FM plant in the Dashiqiao-Haicheng-Xiuyan area ceasing production until 28 May, with only limited restarts.

Small wonder that magnesia supply shortages started to concern traders and consumers both in China and overseas with claims of up to 95% of magnesia production in Liaoning impacted.

Although the inspection team left Liaoning at the end of May, with the exception of just a few, most magnesia producers were still unable to resume full operations.

Only those with both environmental protection equipment (mostly related to de-dusting) and official environment protection certificates have been able to resume production (such as Haicheng Magnesite Refractory General Factory Co. Ltd and Dashiqiao Huasheng Refractory Material Co. Ltd in early June), and even this was reported to be limited to milling/sieving/crushing, no calcination as yet.

It is understood that the central government will send its environmental inspection team back to Liaoning province on 15 August, staying until the end of the month in order to re-assess mineral processing facilities and approve those which have met the environmental protection standards, and thereby give permission to resume production.

Earlier in the year it was reported that all magnesia companies in Yingkou must comply with new environmental standards by 30 September 2017 or face threat of closure.

Owing to these plant closures (and lack of explosives for mining – see below) any fresh production of CCM/DBM/FM has all but ceased.

Magnesia prices in Q2 2017 have doubled, or even tripled by some estimates, over those seen in Q1 2017.

Feeding the magnesia Dragon: a worker tips raw magnesite ore into one of a series of CCM shaft kilns in the Haicheng district of Liaoning province; such plants are now mostly closed following the April/May environmental inspections, and can only restart having met with MEP approval of newly installed environmental protection equipment.

Bauxite & BFA supply also challenged

The anti-pollution drive has affected mineral industries beyond magnesia.

Last week it was reported that 73 Chinese titanium dioxide feedstock plants, about 16% of China’s total production capacity, were permanently closed by the government because they still could not meet the environmental requirements over a period of 12 months.

The upshot is that Chinese TiO2 feedstock prices have increased markedly.

Similar closures have been reported in China’s rare earths, barite, and bauxite sectors.

Regarding calcined bauxite (for refractories, abrasives), the district of Linzhou, Henan has seen around 100 companies required to install environmental protection equipment including compulsory online automated environmental protection reporting.

In Taigu county, Shanxi not one plant met government-set environmental standards and all are now closed until they do.

A bauxite rotary kiln in Jiexiu, Shanxi province, typical of many in the region which will have to install environmental protection equipment before receiving MEP approval to resume production.

Most bauxite rotary kilns in China were shut down indefinitely in May. As in Liaoning, they can only re-start after inspection and permission by central government inspection teams. This has contributed to a constriction in supply of bauxite and brown fused alumina (BFA).

In late July, the MEP instigated its eighth round of strict inspection, which will include six rounds of inspection in Hebei and Henan provinces lasting for 84 days, targeting eight cities in Hebei and seven cities in Henan.

There are two further factors which are contributing to a significant short supply of calcined bauxite.

Firstly, many of the miners subcontracted by Chinalco (owner of nearly all the bauxite mines in Shanxi and the larger ones in Henan) which traditionally supply the best mine-sorted raw bauxite grades to the calciners, have been closed the government.

Secondly, there has also been a series of closures of unlicensed bauxite processing and trading companies, which serve mainly the export market, such as those that proliferate the Xingang port/Tianjin area.

These plants have been closed owing to their lack of business licence, VAT registration or payment, and environmental permits. It is felt unlikely by some that they will ever restart.

Thus, Chinese bauxite is in short supply, with very limited stocks and production, and rising prices with demands of cash in advance payment only.

BFA supply started to tighten at the end of 2016/early 2017 owing to MEP closures of plants in Henan. The situation eased somewhat in April 2017 as plants re-started production with installed environmental equipment.

It is estimated that around 70% of furnaces are probably working in Henan, but only 50% are working in Guizhou.

However, supply of calcined bauxite for fusion plants is now tight and prices are rising, with the prospect of further MEP action compounding the situation.

Bauxite calciners in Sanmenxia, Henan, the main supplier of calcined bauxite, up until now have been running on coal gas, but this is expected to end shortly and disruptions may occur with the move to natural gas.

Those bauxite calciners which have already switched to natural gas have experienced a consequently much higher cost, especially with electricity price rises, 45-50 % of their cost is electricity.

A typical refractory mineral processing operation in Tanggu, Tianjin, receiving raw minerals such as bauxite, kaolin, flint clay for crushing and grinding prior to export from Xingang port. Many such facilities face closure following government inspections.

Dynamite control halts magnesite mining

From 1 February 2017 the central government began to control the supply of explosives for mining, and then officially banned the supply of all explosives within three days of the start of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) and Political Consultation Congress (PCC) on 3 March.

Supply resumed in Liaoning during the second week of June, but apparently to just four nominated mining companies.

Sources in China revealed that explosives are available in the Dandong district, in limited quantity in Dashiqiao, while there is none available in Haicheng and Xiuyan districts. Although some mining can conducted without blasting, most magnesite deposits in Liaoning require drilling and blasting.

Some of the larger magnesite producers have large stocks (>1m tonnes crude ore) which are gradually being consumed in-house by their own calcining plants for their own magnesia production as a first priority.

Owing to the now common practice of not retaining surplus raw material feedstock, independent magnesia plants (ie. not integrated with a magnesite mine) are falling into a critical situation where they are running out of raw material.

The upshot is that magnesite ore is in short supply to Chinese magnesia plants, its price is rising (from US$9-10/tonne to US$40/tonne for domestic users), and as a result Chinese magnesia prices are also rising: for example, magnesite hard burned 90% MgO lump FOB from US$156/tonne in November 2016 to US$330-370/tonne mid-2017.

In Liaoning it is understood that miners are hoping for a resumption of explosives provision at best by September 2017, or mid-October following the 19th National Congress, and at worst, by March 2018.

The problem here is that even the best case scenarios translate to maybe only a maximum two-month period of drilling and blasting before the seasonal closure of mining operations during the winter period of December to March.

New regime of state-managed magnesite ore supply

A new state owned company is to be set up by the Liaoning provincial government on 1 August 2017 to “control the magnesite ore”.

This means that in effect magnesia calcination plants will be required to purchase crude ore from the government in the future.

The prospect of such a scenario was hinted at in June by Christopher Zhao, Chief Investment Officer, Hejun Capital, during his presentation “Current status, challenges, and solutions for China’s magnesia industry” at IMFORMED’s MagForum 2017 conference (see Magnesia market outlook: Krakow crackerjack: Newsfile Report 25 June 2017).

Zhao talked about a range of proposed reforms to China’s magnesia sector including the organisation of a “China Magnesium Group” to better control the supply of magnesite. As expected, this caused much discussion in the following Q&A session. Now it seems Zhao’s prediction was spot on.

However, it is understood – perhaps not surprisingly – that there remains a range of issues to be resolved between the Liaoning government and the magnesia producers. It is not yet clear what kind of limitation or regulation will be enforced in the near future.

Indeed, this next step, which is significant, and with it perhaps enforcement of some kind of control or even new tax, is potentially the much warned and talked about “substitute” for the dropped export tax and quota system at the start of the year.

It is also worth noting that although the export quota policy as such was cancelled, companies who continue to export CCM/DBM/FM with a content > 70% MgO, still need to apply for a compulsory export licence or “quota certificate for exporting”, albeit without charge (also applies to brucite).

In this way, the authorities can keep track of export volumes, even though there is no imposed limit.

What of the future?

Great question: “Nobody knows if, when, and how this will play out. It’s not clear how/if this situation will improve/get worse/be mitigated. We are in a period of uncertainty. What is clear is that these problems causing the shortage will not be solved quickly, and have been completely underestimated by the foreign traders and some customers.” says James Devlin, Managing Director, CMP.

The real question is perhaps whether all or any of these mineral operations can successfully resume production, and at what rate of utilisation?

In a recent presentation to the refractories industry, Devlin revealed the following stipulations by the MEP to Chinese mineral processing companies:

• only use natural gas and/or electricity for energy supply; no coal, coke, or coal gas

• install approved systematic on-line externally monitored dust control system

• install approved systematic flue gas desulphurisation control system

The problem is that such equipment is expensive, difficult to install, and not instantly available. Moreover, many plants are too old or in such a condition as to be unfit for such upgrading.

Just to give a clue as to the scale of the problem facing China’s attempt to clean up its industry: during the seventh round of the year-long strict inspection on air pollution control in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area alone, during 7-20 July 2017, a total of 5,322 businesses were checked and 1,389 were found to be environmentally non-compliant.

Of the non-compliant enterprises, 347 were unlicensed small polluters, two did not attain emission standards, 252 failed to install pollution control facilities, 160 failed to keep such facilities in normal operations, 536 had VOCs control problems, and four had “other” problems.

It might be the case that although the environmental issues could be resolved to some extent, and even this may well be limited to just the larger, smarter, and more modern players, the mining explosives issue looks to be a huge problem for the near and medium term.

Without consistent, good quality crude ore to feed calcination and other mineral processing plants, it seems likely that the market should expect continued shortages and high prices of minerals such as magnesia, bauxite, and BFA grades.

So China’s mineral industry is facing a likely period of massive rationalisation and consolidation as inefficient and old plants are closed down, and reforms on supply control put in place – not entirely a bad thing by any means. Let’s wait and see.

But combined with a parallel restriction in mining fresh crude ore owing to explosives control, this will surely foster continued shortages of key industrial minerals for export well into 2018.

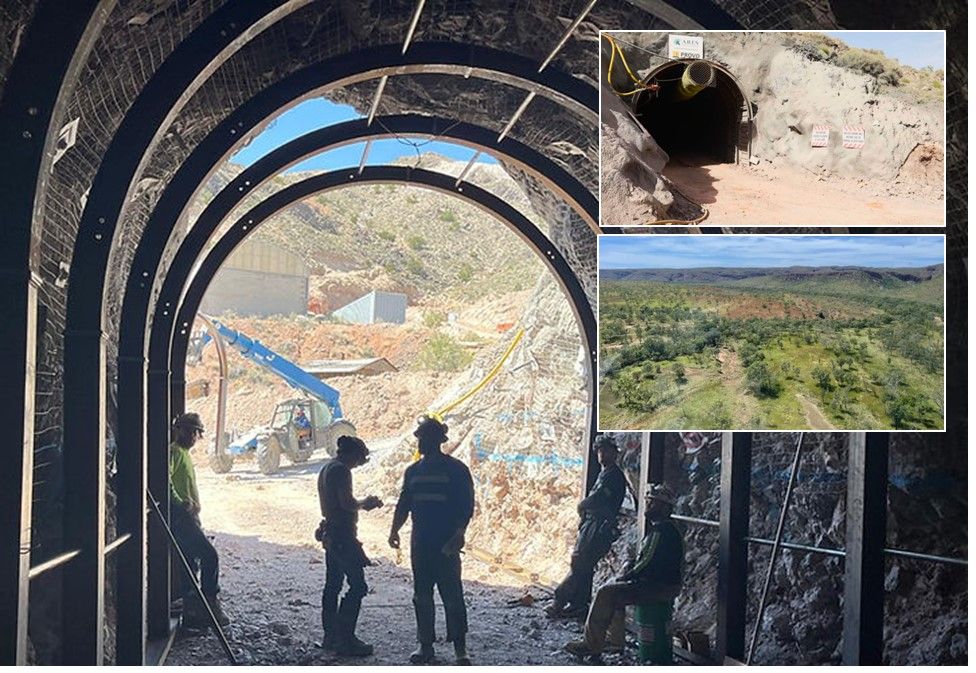

This is just as much a headache for mineral traders and consumers as it is a golden opportunity for mineral producers and developers outside China.

Don’t miss these key events to keep your business updated with the latest developments in Chinese minerals supply and meet with the leading players

DETAILS HERE

DETAILS HERE

DETAILS HERE

Excellent article.

Great article Mike. It would appear that export of industrial minerals from China will be more difficult in the future and the age of cheap Chinese raw materials is now over. Development of non Chinese industrial mineral raw materials will become more important and a necessary strategy for non Chinese customers of industrial minerals.

Another interesting article in European Coatings illustrating the pollution controls now underway in China

“73 Chinese TiO2-feedstock plants are being permanently closed by the government. The plants “still cannot meet the requirement from China Environmental Protection Administration after 1 year’s measures”

An excellent article Mike. For the fused products, such as fused magnesia and fused alumina, there is an additional problem. An acute shortage of graphite electrodes, with a consequent price increase of 400% to 500%. And even at the higher prices you need to wait in line for supply.