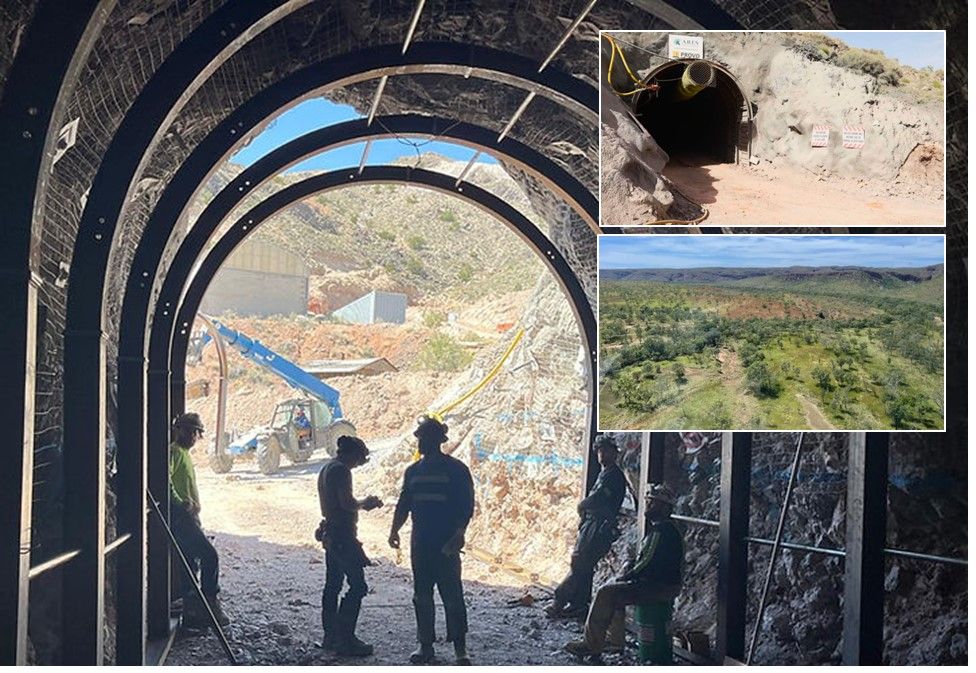

The frac pad at San Leon Energy’s Lewino-1G2 well in Poland’s northern Baltic Basin. Described as “the best single frac in a vertical well in European shale”, the operation used 30/50 mesh ceramic proppants. Engineering for a horizontal multi-fracking operation is continuing. Courtesy San Leon Energy Plc.

Further withdrawals by overseas oil and gas exploration companies from Ukraine is seriously hindering the country’s ability to swiftly realise its shale gas resource potential, and thus provide a potential market for proppants.

That said, the two European countries holding the brightest torch for unconventional oil and gas resource development are the UK and Poland.

In early January 2015, two UK companies, JKX Oil and Gas Plc and Regal Petroleum Plc each announced that they were reviewing shale gas activity in Ukraine owing to government regulations which are claimed to be hindering exploration and extraction efforts.

The companies’ decision follows the withdrawal of Chevron which terminated its $10bn agreement with the Ukraine to develop the country’s shale gas reserves in December 2014.

In November 2013, Chevron signed a long-term shale investment deal with the government. The company had reaffirmed its interest in developing the industry during 2014, but it appears that regulatory obstacles, the worsening geo-political situation, and the more recent falling oil prices may have tipped the balance.

Ukraine was looking to be a clear hot spot of shale activity with both Chevron and Shell signing deals with Kiev in 2013 to develop unconventional gas in the country. The most prospective areas for coal bed methane production are in eastern Ukraine, while shale gas is being explored in the Lubin basin, which extends from western Ukraine into Poland, as well as in the east of the country.

Shell has since postponed its activities in Ukraine for two years owing to the country’s future uncertainty. For now, any activity here is surely on hold until the regulatory environment improves and political issues stabilise – but it should not be ruled out for the future.

The Russian factor

In late 2014, extraordinary accusations were being aired in Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Romania levelled at Russian energy giant Gazprom for allegedly supporting protests against fracking in these countries – pouring more cold water on the market for budding proppant suppliers in Europe.

Romania had been one of the potential shale gas development targets in Europe, hosting the third highest shale gas reserves in the EU according to the US Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) estimates (although these estimates have since been downgraded).

Things were looking promising. In early 2013, Romania reversed its earlier freeze on fracking, and the government supported the development of shale gas and signed a deal with Chevron. In mid-2014, the company completed shale gas exploration in the Silistea-Pungesti perimeter in eastern Romania.

However, although Chevron has yet to complete its assessment of Romania’s shale gas potential, early November 2014 saw Prime Minister Victor Ponta announce rather dramatically, “it looks like we don’t have shale gas” – placing a dampener on proppant market prospects in the country.

With these more recent claims of Russian involvement in anti-fracking activity, the future for further shale gas development in Romania is uncertain.

The geopolitics of Russian gas supply

Certainly, Russia has much to lose from seeing its existing and extensive gas supply customers in Europe switching to their own domestic supply fed by shale gas exploitation. So a movement to prevent or hinder hydraulic fracturing operations in Europe would perhaps not be unwelcome by Russia.

Europe imports about 30% of its natural gas from Russia, of which more than 50% flows through Ukraine. The issue of reliance by some states on gas supplied by Russia has come into the spotlight with this year’s conflict escalation in Ukraine.

Poland and Ukraine, among others, for some time have used the issue of natural gas import reliance on Russia as a driver for developing their own shale gas resources. This trend has now been given added impetus by events in Ukraine, which have already led to reduced Russian gas supply to Poland, and a complete supply halt to Ukraine.

It has got to the point that the EU member states are now stockpiling gas in record quantities as they prepare for the possibility that Russia may turn off gas exports to Europe, as has been threatened.

If one follows the threat of a potential cut-off from Russian gas, the countries most affected, and thus requiring an alternative gas supply will be Finland (100% reliant), the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, all 100%), Poland (79.8%), Czech Republic (99.5%), Slovakia (100%), Romania (86.1%), Ukraine (100%), Austria (71%), Bulgaria (100%), and Turkey (58%).

The issue has clear implications for potential shale gas development in Europe, and a number of players are already assessing options of establishing proppant supply sources.

So where are such shale gas development and proppant demand hot spots likely to be in Europe?

Potential proppant hot spots

A number of EU countries are in the process of granting or have granted concessions and/or prospection/exploration licences for shale gas plays over the past three years, these are: Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden and the UK.

However, only Denmark, Germany, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the UK have seen any actual activity, albeit limited (initial prospecting/exploration). Germany has a moratorium on further fracking in place, but there is talk that this may be lifted in 2019.

Poland and the UK appear to be leading the pack with shale gas development and government support. However, they maybe followed by others in the near future, Romania was thought to be a favourite.

Bulgaria and the Czech Republic have unconventional resources but still have bans on hydraulic fracturing in place, although the Czech ban was to be reviewed in 2014. How the situation with Russian gas supply may influence this remains to be seen.

In Austria, there is identified potential for large shale gas reserves in Lower Austria which could meet Austria’s energy demand for 30 years. Austria is home to energy giant OMV AG, which in 2012 abandoned its plans to drill shale gas resources in the country. This decision may now be revisited.

Turkey is looking to be quite attractive, with Royal Dutch Shell Plc, TransAtlantic Petroleum Ltd, and Valeura Energy Inc. among explorers initiating plans to drill shale resources hosting 4.6 tcm of gas and 94 bn bbl of oil, according to the EIA.

The country has two main benefits attractive to development: much of the land with potential unconventional deposits is sparsely populated, thereby incurring little opposition to drilling operations; and Turkey’s new petroleum law, passed in 2013, removed territorial restrictions on exploration and opened the country for international companies, further enhanced by a more attractive fiscal system.

Polish setbacks but shale interest prevails

Poland, long considered Europe’s leading beacon for shale gas development, has suffered a recent setback in confidence from the energy majors. Eni, Exxon Mobil, Marathon Oil, ConocoPhillips, 3 Legs and Talisman Energy have withdrawn from Poland after an initial burst of interest, citing a range of reasons, including the regulatory environment and complex geology. Chevron, however, has remained in Poland.

Nevertheless, the Polish government is supporting shale gas development and plans to invest $17bn by 2020 in the shale gas sector and has reviewed its fiscal framework to attract investors.

The total number of shale gas wells drilled in 2014 was expected to increase to about 80, compared with 13 in 2013. According to Maciej Grabowski, Poland’s environment minister, the country needs at least 200 wells to test its shale gas potential.

There remains a fair degree of activity in Poland. Dublin-based San Leon Energy is forging ahead with drilling activity in Poland. The company’s Lewino-1G2 test well in northern Poland has sustained gas production rates of 45,000-60,000 standard cubic feet per day.

Lewino-1G2 underwent a vertical fracturing programme comprising three fracture stages, the last of which was refined to provide higher proppant concentrations, of 4lbs/gal, using a 30/50 mesh ceramic proppant. This was the first fracture treatment in Poland to use ceramic proppants. The next phase will be a 1,500 metre horizontal multi-stage fracture.

Elsewhere, San Leon has concessions in central Poland where new drilling is to commence at the Rawicz field development and fracking operations at the Siekierki Project’s Poznan East and North wells. In 2014, San Leon signed a letter of intent with Baker Hughes to conduct fracturing in these wells.

In early January 2015, BNK Petroleum reported positive results from further well testing at its Gapawo B-1 H well in Poland’s Ordovician shale play, and intends to conduct further exploration and to seek partners in joint investment ventures.

UK starts to invest heavily in shale gas outlook

Finally, the UK can also be considered a potential hot spot for proppant demand. Unconventional resources targets include the Bowland-Hodder unit across north England, the Midland Valley, Scotland, and the Weald in southern England.

There has been much activity surrounding political moves and legislation encouraging shale gas development, but little operational activity to date.

This may be set to change with a number of key players jostling for position to exploit auctioned UK oilfield licences. These include IGas, GDF Suez, Total, Cuadrilla Resources, Ineos, Dart Energy, Egdon, Celtique Energie, Eden Energy, and Centrica.

IGas has an ambitious exploration plan for the Liverpool-Manchester area of north-west England which envisages the development of 30 shale gas production sites, each site comprising 10 vertical production wells each with 4 horizontal laterals (ie. 40 laterals per production site).

IGas also announced an increase in its UK shale gas project estimates to now range between 34 tcf and 263 tcf, with 147 tcf deemed the “most likely”.

The UK shale gas industry received a high profile boost in late 2014 when international chemicals giant Ineos pledged to invest £640m in UK shale development, as part of plans to use the shale gas in its UK chemical plants.

In December 2014, Egdon Resources and Scottish Power announced plans to move ahead with a UK joint shale venture, following positive seismic data testing.

Cuadrilla is in the final stages of its planning application process for up to four shale gas exploration wells at each of its proposed sites at Roseacre Wood and Preston New Road, both in Lancashire, north-west England.

Although early days, the likelihood of significant proppant demand in Europe for drilling programmes to exploit unconventional oil and gas resources is edging closer.

Poland and the UK are clearly leading the pack, with Romania, Turkey, and the Baltic states following some way behind.

2015 will be a crucial year in order to assess the feedback from the planned drilling programmes in Poland and the UK, and could possibly herald the start of Europe’s proppant market from 2016-17.

Proppants are the subject of several key presentations at IMFORMED’s Oilfield Minerals & Markets Forum Houston 2015, 27-29 May 2015:

Oilfield minerals: supplying the market

Dave Fattaroli, Chief Commercial Officer, Unimin Energy Solutions, USA

Proppant market demand outlook

Samir Nangia, Principal, PacWest Consulting Partners, USA

Frac sand: US exploration and production – where’s it heading?

Mark Zdunczyk, Consultant Geologist, USA

Chinese proppants supply & markets

Gene Kim, CEO, AM2F Energy Inc., USA

Frac sand developments for the Argentinean shale gas market

Richard Spencer, President & CEO, South American Silica Corp., USA

Ceramic proppant development using fly ash as raw material

Siegfried Konig, Executive Director, Coretrack Ltd, Australia

Leave A Comment