North American mineral prospects – so who’s doing what?

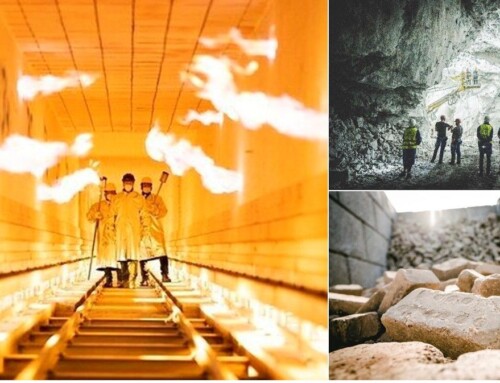

Drilling core samples at the bottom of one of the pits on the Lost Sheep Mine property, Utah; a historic fluorspar mining area, Ares Strategic Mining is looking to bring it back on stream. Courtesy Ares Strategic Mining

New fluorspar deposit development and progress with alternative fluorine sources such as fluorosilicic acid (FSA), depleted uranium hexafluoride (DUHF), mine tailings, and aluminium fluoride (AlF3) from bauxite are all receiving increasing attention.

Although the world economy and industry is understandably experiencing a slowdown owing to the ramifications of the Covid-19 virus, recovery, albeit patchy in places and perhaps far from rapid, is nevertheless expected to materialise.

When we do emerge from the other side of this challenging and tragic episode, the fluorine industry, like any other, wishes to be fit for action – and this includes having sufficient supply sources on stream to meet market demand.

During 2019 the fluorspar market was in good health and the supply-demand situation was relatively tight for much of the year. Coming into 2020, there were signs that the global economy was slowing and demand was starting to wane, Covid-19 has now since exacerbated this.

At IMFORMED’s Fluorine Forum 2019, in Prague last October an audience poll voted “tight supply” as the market’s key challenge (see Pitch Perfect in Prague for a review).

PLEASE NOTE

We are pleased to announce that we aim to run Fluorine Forum ONLINE 2020 this year:

Fluorine Forum ONLINE 2020

13 October 2020

Full Details

Our Fluorine Forum October 2020, Hanoi, has been

postponed to 18-20 October 2021, Pan Pacific Hanoi

Visit to Masan Resources’ Nui Phao operation Thurs. 21 October 2021

Full Details

Moreover, on the question of “Emerging new fluorspar supply: can the market absorb this extra capacity?”

- 56% voted “Yes, easily; in fact we need additional new suppliers”,

- 32% agreed “Yes, the market needs at least two new suppliers”

- 12% “No, we don’t need the extra capacity.”

Although Fluorsid owns subsidiary fluorspar miner British Fluorspar, the group is seeking to secure alternative sources of raw material supply to meet consumption requirements. Courtesy British Fluorspar

So, clear signals that new sources are required, and beyond the two most recent newcomers which eventually came on stream in 2019, although not without some (ongoing) difficulties: Canada Fluorspar Inc., in Newfoundland, and SepFluor Ltd in Gauteng, South Africa.

At the conference, Italian fluorochemical group Fluorsid underlined this by revealing that is to embark on exploration and development of fluorspar mining capabilities in order to improve its security of raw material supply, seeking captive sources in Europe and overseas – a prospect in South America is apparently under development.

Oliver Rhode, CEO, Xenops Chemicals GmbH & Co. KG, Germany, commented during his presentation: “Overall, the fluorspar market remains tight, even when the new producers are running at nameplate capacity next year. There are new projects, but it is not clear when they will start commercial production.”

Also last year, GFL GM Fluorspar SA, a subsidiary of leading Indian fluorspar consumer Gujarat Fluorochemicals Ltd (GFL), announced an expansion of production capacity of acid grade fluorspar (acidspar) at its Taourirt operation in Morocco (see New fluorspar source for European markets).

Sure, most producers will perhaps not be running at nameplate capacity right now (although certain major suppliers reported that they are maintaining healthy sales), and it may seem daunting to embark on developing a new deposit at this time.

But while the global supply-demand dynamic somewhat eases in this enforced “quiet period”, maybe it is the ideal time for developers of new fluorine sources to crack on and aim to bring their projects to fruition in time for market recovery later this year, or early 2021.

Added impetus will not only come from market trends (see below), but also from rising concern on over-reliance of China as a source of minerals (see China’s mineral supply to global markets: dominance, diversity & disruption), and fluorspar’s classification as a “critical” or “strategic” mineral, most recently recognised and federally reinforced in North America.

Impact of COVID-19 on the fluorspar industry and discussion on threat of alternatives to fluorspar

Webinar organised by

| panel participation by

Thursday 25 June 2020

Roskill will present its latest views and insights on the fluorspar industry and the entire F-supply chain, examining the challenges caused by COVID-19 given the impact the pandemic is having globally and what the future may have in store based on Roskill’s in-house macroeconomic outlook.

The webinar will also host a panel with special guest Mike O’Driscoll of IMFORMED; and Adam Coggins and Kerry Satterthwaite, Fluorspar Analysts at Roskill, with a deeper look at the fundamentals of the acidspar and metspar markets in light of the global economy, and how supply chains may be reshaped to reduce risk from future pandemics or similar events.

Asia and Oceania

0800 AM BST

REGISTER HEREEurope, Africa and Americas

03:30 PM BST

REGISTER HEREThere will be an opportunity for Q&As at the end of the call.

To submit questions in advance, please contact Kerry Satterthwaite: kerry@roskill.com

Key drivers: China switches to a fluorspar consumer | Li-ion batteries

In addition to a return to overall tight supply, specific key drivers include the lessening influence in supply to world fluorspar markets from Chinese sources, and in turn, increasing Chinese domestic market demand, especially from fluorochemical production, prompting the potential of selling fluorspar to China (China is already a net importer of metspar, acidspar soon to follow?).

China’s fluorspar supply sector has continuing challenges such as: mining license renewal delays, temporary and permanent shutdowns, closure of most small-sized mines, unsustainable utilisation of low-grade ores, and many mid-/large-sized mines are now entering ore depletion phase.

There were just 251 mines by the end of 2018, down from >1,200 in 2013. Moreover, there is a lack of new sizable mines and resources and raw ore is being imported from Mongolia.

While HF and fluorochemical markets, steel, and aluminium remain the primary consumers, another emerging driver is from new downstream industries, specifically Li-ion batteries (LIB) in electric vehicles (EVs).

LIB use an electrolyte comprising the fluorine containing compound LiPF6. By 2040 it is estimated that some 100-153,000 tonnes of LiF will be required to meet LiPF6 demand.

The primary anode raw material for LIB is flake graphite, which is processed to battery grade spherical graphite. Graphite processing requires acid leaching with HF acid, derived from fluorspar, and thus another potential market driver from EV evolution.

However, although using HF is the main process route employed in China (and elsewhere) for production, it must be noted that graphite developers outside China are keen to develop proprietary alternative and greener methods not using HF acid.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, at the end of 2019 there were 119 EV LIB plants announced in the pipeline worldwide, a significant increase from 63 in 2018.

Europe has surged ahead in planned LIB capacity for its EV industry by 2029, planned at 348GWh by the end of 2019 (China continues to dominate adding 564GWh by 2028; total lithium ion battery capacity in pipeline equals about 39m EVs by 2029).

So who’s doing what? Potential North American sources in the pipeline

Ashram Deposit, Quebec – Commerce Resources

Vancouver-based explorer Commerce Resources Corp. is focused on the development of the Ashram rare earth and fluorspar deposit, claimed as one of the world’s largest, in the Nunavik territory of northern Quebec, about 100km south of Kuujjuaq.

The PFS is at an advanced stage, and a PEA in 2015 identified a measured resource of 1.59m tonnes averaging 1.77% total rare earth oxides (TREO), a 45%+ TREO concentrate has been produced from the deposit.

While the PEA envisaged an operation producing 16,850 tpa of REO for 25 years, fluorspar is now being assessed as an important by-product processed from the tailings of the primary REE mineral concentrate.

The Ashram Deposit is hosted by the Eldor Carbonatite and its main mineralogy comprises monazite (57.0%), bastnaesite (13.8%), and fluorite (11%). Fluorite is typically abundant and pervasive in the most highly mineralised A-zone of the Ashram Deposit, occurring as disseminations, blebs, patches, veins, and fracture fillings.

Test work in February 2020 resulted in successful upgrading of the Ashram fluorspar content to a purity of 97.8% CaF2, (acidspar requires min. 97%). Testing will now focus on impurity removal as well as improved fluorspar recovery.

Tailings characterisation test programmes are ongoing, as is beneficiation test work in collaboration with CanmetMINING and Corem. Most recently, CanmetMINING identified an alternative reagent scheme and flotation circuit to achieve, and potentially exceed, the target objective of <25% mass pull at >80% recovery using a much reduced volume of reagents.

In April 2016, Commerce Resources signed a binding MoU with NorFalco Sales for supply of sulphuric acid for the project.

The Ashram project appears to have potential as a fluorspar source since (as in the successful development of Masan Resources‘ Nui Phao fluorine containing polymetallic deposit in Vietnam) it has the crucial advantage of it being a by-product of high demand commodity, in this case rare earths.

Both rare earths and fluorspar are deemed critical and strategic minerals for Quebec with their use in renewable energy industries, and also for fluorspar, in the aluminium industry.

Lost Sheep Mine, Utah – Ares Strategic Mining

The Lost Sheep fluorspar mine and its surrounding claims (the Lost Sheep Property, LSP) are located at the Spor Mountain area, Juab County, Utah, approximately 214km south-west of Salt Lake City. The project consists of 67 claims spanning a 5.9 km2 area.

Initially under Lithium Energy Products Inc., which started ramping up finance for the Lost Sheep mine in November 2019, the asset was acquired by Vancouver-based Ares Strategic Mining Inc. (ASM) in February 2020, which is aiming to rejuvenate this previously mined fluorspar property.

ASM states that the mine is fully permitted, it has secured offtake agreements with multinationals (including a two-year 60,000 tpa metspar MoU with Possehl Erzkontor North America Inc.), and has “ambitions to create a large mining operation, capable of producing industry-grade metspar and acidspar for the world markets”.

The proposed US$3m expansion plan involves purchasing and installation of an automated development of adit, ball mill, DMS plant, flotation system, bagging facility, a second warehouse and loading bay, and leasing loaders, dump trucks, and dozer. An initial 50,000 tpa metspar production for 10 years is envisaged.

Fluorspar mining in the LSP district dates back to 1943, with over 350,000 s. tons of ore shipped from 29 deposits, the vast majority from the Lost Sheep Mine (LSM) during 1948-2007, with most activity and peak production in the 1950-60s.

The LSM comprises 10 claims (10) and 70km south-east is a processing plant and warehouse in Delta, Juab County, Utah, with a Union Pacific railroad siding. In 2017, the LSM was listed as active, and the only remaining fluorite producer in the district.

According to a Technical Report in 2019 by Antediluvial Consulting Inc., the LSM produced ore from three breccia pipes, selectively mined yielding a metallurgical grade of 60-95% CaF2 sold to steelmakers.

Most early production was run of mine ore and shipped to the Geneva Steel plant at Vineyard, Utah County. After 1990, ore was crushed and screened before shipping in 50lb bags by truck.

Cumulative production at LSM from 1948-2014 has been estimated at 169,744 s. tons of ore. Production officially ended in 2007, although minor extraction is claimed to have occurred 2008-2017 during periodic attempts to re-start the mine by the property owners and Clearwater Group.

Certain shipments of LSM ore in the 1950s were recorded to show grades of 90-95% CaF2. The key question will be whether more of the same exists and at economically recoverable volumes.

Amazingly, despite this rich history of development and mining, the property has received no systematic exploration, geological mapping, sampling or drilling, and thus there are no resource or reserve estimates.

The principal exploration targets are breccias and pipes hosting fluorite mineralisation located within faulted dolomite and associated with volcanic intrusions.

A recent report on the project by Alphabridge states that “the first two pipes that the company is working on delineating are expected to contain at least 150,000 tons of fluorspar.”

In late May 2020 ASM announced an $800,000 Private Placement Financing which will be primarily used to fund exploration activities, permitting, engineering and economic studies for the LSM.

ASM’s Phase 1 drill programme was completed by 2 June 2020 confirming the location, size and orientation of one of the fluorspar pipes located on the property. The pipe has an approximate surface projected dimensions of 60 x 30 metres and was tested to a depth of just 80 metres, where it remains open for potential extension.

A “Glory Hole” at the Lost Sheep Mine, Utah, with purple fluorite mineralisation showing clearly. Courtesy Ares Strategic Mining

Drill results are being used in combination with LiDAR for mine design and operational planning to inform the mining operation scheduled for later this year.

Samples assays expected to be received by the company in July. With the drilling data ASM is preparing production plans in combination with processing work currently underway to produce acid grade fluorspar for the US market.

Of significant interest is a recent Chinese connection with the LSM. In March this year, ASM entered into strategic partnership with the Mujim Group, a Shanghai-based fluorspar producer and trader, with production facilities in China, Thailand, and Laos, and claiming 150,000 tpa in sales.

Following a visit to the LSM, Mujim Group agreed to invest time and expertise in assisting ASM with equipment selection, mining methods, processing techniques and the supply of expert fluorspar mining personnel.

Of course it remains early days, but is there any prospect that the LSM could grow to be a fluorspar source for Chinese markets?

Meanwhile, ASM has sought to extend its fluorspar portfolio by entering into a Definitive Agreement to acquire 100% of the Liard Fluorite project, described as “the most significant fluorite prospect in British Columbia.” Previous exploration work has indicated grades in excess of 30% purity fluorspar.

MB Project, Nevada – Tertiary Minerals

Tertiary Minerals Plc, London has been evaluating a major fluorspar deposit in Nevada. The MB Project claims are located 19km south-west of Eureka in central Nevada, and have been previously explored for beryllium and other minerals, but not specifically fluorspar, despite its discovery in drill results.

Since 2013, there have been four phases of drilling, resulting in 2015 in a mineral resource estimate of 6.1m tonnes at 10.8% CaF2 indicated, and 80.3m tonnes at 10.7% CaF2, inferred, at 9% CaF2 cut off.

Tertiary has commenced a programme of scoping level metallurgical test work at SGS Lakefield in Canada aimed at improving recoveries and concentrate grade for fluorspar mineralisation in the Central Zone of the deposit.

In its latest report, 29 May 2020, Tertiary acknowledges that this work “has been problematic and a breakthrough is needed if the potential of this large low-grade resource is to be realised.”

(The company’s Storuman fluorspar project, Sweden, 27.8m tonnes at 10.2% CaF2, metallurgical recovery of 81.9%, with a conceptual output of 100,000 tpa acidspar, remains on hold pending resolution of the project’s Exploitation (Mine) Permit – initially, granted, then refused, against which Tertiary lodged an appeal in May 2019.)

Hicks Dome, Illinois – Hicks Dome LLC

The Hicks Dome rare earth and fluorite occurrence, described as a cryptovolcanic feature and an “igneous exploded breccia”, is near Herod, Hardin country, south Illinois, and historically has been associated with the Illinois-Kentucky Fluorspar Mining District.

The deposit, frequently referred to as a very large one, was discovered in the early 1900s, and fluorite mined in the 1930s, since when there has been no production and activity limited to a succession of small-scale exploratory drill programmes, and routine claim maintenance. According to a USGS report in 1978, a limited drilling programme indicated 11.3m tonnes at 11.5% CaF2.

Fluorite mineralisation at Hicks Dome is found in breccias that also contain substantial concentrations of beryllium, niobium, REEs, thorium, and yttrium, as well as local concentrations of zinc, lead, and barite. The ore body is pipe-like in shape of unknown dimensions.

Hicks Dome LLC (supported by Red Abbey LLC), applied for permits to drill three holes in the deposit in 2015, and drill core samples have indicated fluorspar concentrations of 20-33% fluorspar. The company is engaged in cooperative studies with the USGS and Illinois State Geological Survey. Any further test work and drilling is on hold, as the company assimilates data to date and assesses potential processing and/or JV options.

Klondike II, Kentucky – Hastie Mining

Hastie Mining & Trucking Co., based in Rosiclare, Illinois, has been in the fluorspar business since 1965, with limestone and fluorspar operations in Cave-in-Rock, Elizabethtown, and Rosiclare, Illinois; New Kensington, Pennsylvania; and Salem, Kentucky.

During the last decade or so, Hastie’s activity has been limited to producing metspar as a by-product from its Cave-in-Rock limestone operation (reports suggest in the order of 10,000 tpa, although output appears to be intermittent), as well as marketing and distributing screened and dried imported acidspar and metspar.

The Hastie open pit mine at Cave-in-Rock extracts Mississippian Ste. Genevieve Limestone for aggregate and construction use, and is mining through an area hosting abandoned underground fluorspar workings.

However, according to the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet’s Aggregate Source Book (June 2020), the Cave-in-Rock facility is classed as “inactive”.

Since 2010, Hastie has been striving to bring on stream a new fluorspar mine, the Klondike II, in a historic fluorspar mining area between Burna and Salem, Livingstone County, Kentucky. The large, rich vein deposit, hosting 3.5m tonnes of reserves (a vein resource of at least 1.6m tonnes of ore grading 60% CaF2 was reported in 2009), promised higher quality raw material yielding both metspar and acidspar grades, and there were plans for a potential 50,000 tpa fluorspar output by 2018.

Some US$3m was invested into the project; the company installed heavy-media gravity separation and briquetting equipment at its Cave-in-Rock limestone plant in Illinois for processing the Klondike ore, and some years earlier had acquired a flotation plant near Salem, although this requires extensive renovation to become operational.

However, the Klondike II project has been dogged by delays and remains unrealised. Some 20,000 tonnes had been mined and stockpiled by 2015. Latest USGS reports indicate that development of the project is ongoing, although to what extent remains unclear.

Wrap-up

Apart from the MB Project in Nevada, the other prospects fall into two common camps: either they were subject to earlier exploitation for fluorspar, or they are associated with potentially valuable commodities, ie. rare earths, thorium.

Certainly, having a valuable co- or by-product enhances the prospects of the project’s success. And in revisiting previously worked fluorspar districts, with modern exploration techniques and significantly superior processing methods, there is the chance that a good economic grade could be realised. We shall have to wait and see.

In Part 2 Fluorine focus: new & alternative source developments we shall examine the latest developments from alternative fluorine sources to primary mineral deposits, ie. fluorosilicic acid (FSA), depleted uranium hexafluoride (DUHF), mine tailings, and aluminium fluoride (AlF3) from bauxite.

A 60-second scan of key market elements. Stripped down to the basics. All you need to know in a minute.

- Overview

- Composition & Key Properties

- Geology & Occurrence

- Processing

- Grades & Applications

- Sources & Production

- Price Indicator

- Market Drivers & Trends

CLICK HERE FOR FREE PDF DOWNLOAD

PLEASE NOTE

We are pleased to announce that we aim to run Fluorine Forum ONLINE 2020 this year:

Fluorine Forum ONLINE 2020

13 October 2020

Full Details

Please note: Fluorine Forum October 2020, Hanoi

postponed to 18-20 October 2021

Visit to Masan Resources’ Nui Phao operation Thurs. 21 October 2021

Full Details