Industry heads to MagForum 2017 Kraków for answers and latest outlook

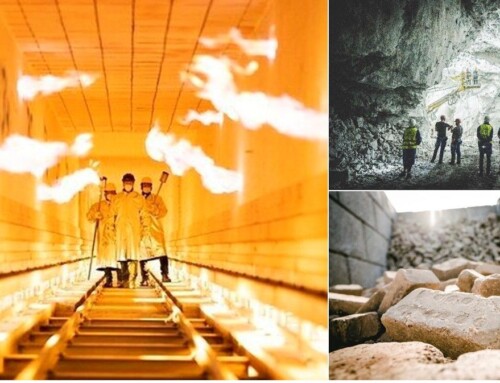

Fusing magnesia in Dashiqiao, Liaoning province; production has been dramatically reduced owing to pollution inspections in the province, prompting shortages in supply for export and domestic markets.

Accounting for about 70% of world magnesite production and just over 60% of world magnesia production, China has a strong influence over the global magnesia market.

But even by its normal, and frequently unpredictable standards, China has ensured that the magnesia industry will already remember 2017 as an extraordinary year even before we hit the halfway mark.

Right now, robust government anti-pollution measures reaching out across the country’s mining industry has prompted the closure of many magnesia calcination and fusion plants in Liaoning province, China’s centre of magnesia output.

This has led to a squeeze on material availability and concern over the future of China’s production capacity situation for magnesia supply.

A few operations are now just returning to production after having met environmental protection measures, Haicheng Magnesite Refractory General Factory Co. Ltd and Dashiqiao Huasheng Refractory Material Co. Ltd among those.

Magnesia mineral market trends and outlook

The only place to be: All you have to know, All you have to meet

Over 170 delegates already registered

MagForum 2017, Radisson Blu Hotel, Kraków, 11-14 June 2017

Visit to ZM Ropczyce’s refractory plant

Click here for programme | Register Now!

Contact Ismene +44 (0)7905 771 494 | ismene@imformed.com

The anti-pollution crackdown was always in the offing for the magnesia industry, and is not the first of its kind to hit Chinese refractory minerals.

Bauxite and fused alumina producers in Shanxi province suffered similar issues over a decade ago when they witnessed the government induced demise of the widespread and popular, but environmentally unfriendly, traditional shaft and round kilns (in favour of modern rotary kilns). Shanxi’s calcined bauxite sector is now undergoing another round of pollution inspections and closures.

However, the double whammy for the magnesia market this year was not just the environmental legislation, but the dropping of the export quota system and export taxes for magnesite and magnesia.

In utterly typical fashion, the Chinese mineral industry’s most significant gamechanger for export trade was shrouded in confusion, misinformation, and little, if any clarity. Plus ça change!

The initial upshot of this long-awaited and debated move, was an increase in magnesia export volumes and a lowering of prices at the start of 2017.

However, this was followed by the impact of pollution inspections and the resulting stoppages in supply has since firmed up some prices of dead burned and fused magnesia, and traders have reported some quite haphazard pricing.

Chinese magnesia exports: when Beijing took control

Since its inception in 1994, China’s Export Licence System for selected mineral commodities had dogged the lives of mineral traders and consumers across the globe.

Initiated on 1 April 1994, largely in response to falling foul of antidumping duties in Europe, to better control its exports, and claimed to help control exploitation of domestic resources, this was no April Fool as the Chinese government sought to administer exports of 13 minerals including magnesite and magnesia.

In addition to placing a total quota on the export volume, potential exporters were required to bid against each other for a licence to export, and if successful were required to pay the licence fee (RMB/t exported).

There were only a limited number of licences available and this was to be conducted twice a year for each half of the year’s total export volume.

Bayuquan Port, Liaoning is one of the main conduits for Chinese magnesia exports to global markets.

It was, in effect, a “mineral tax”, and craftily pitched the onus on exporters and traders to sort themselves out and play them off against each other.

In later years, further tax burdens followed such as the abolition of VAT rebate, a resource tax, and export tax.

The outcome, unsurprisingly, was chaotic, and not helped in successive years with irregular and confused tweaking of the system which stretched the nerves of the trading community as they awaited the latest evolution of the system, traditionally announced last minute on 31 December each year.

While laudable in an effort to avoid dumping mineral exports in the West, the Export Licence System served to frustrate export trade and prompted widespread issues:

- prices rose and became unpredictable

- some Chinese producers failed to secure licences and could not export

- those that failed in the 1st round then bid higher licence prices in the 2nd in order to win licences

- collusion between players, and an underground “horse-trading“ in licences emerged between the “haves” and “have-nots”

- traders were unable to guarantee prices and volumes to customers

- at the end of each half year period, unused licences were subject to a “fire sale” so as to avoid paying penalites for unfulfilled export quotas (plus prohibition to apply in next round), thus skewing price levels

- magnesia export smuggling through several methods became rife to avoid export licences and taxes

Since this author broke the news of the export licences in 1994, he has witnessed debate over its administration (by the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters) and possible cancellation (especially over the last few years) on an almost annual basis.

In 2016, the export volume quota for magnesite was 1.7m tonnes, and the export licence was quoted at RMB140-330(US$20-48)/tonne. Export tax was 5% for CCM, and 10% for DBM and FM.

Chinese magnesia exports: the Dragon turns

Things came to a head last year with the US and the EU filing separate cases with the WTO against Chinese export duties on several minerals and metals, including magnesia.

These were just the latest of several such cases over the years lobbying the WTO to pressure China to tidy up its trade practices, leading to the cancelling of export taxes on some commodities already: bauxite, fluorspar, silicon carbide in 2009; and rare earths in 2015.

Another factor which may have influenced the decision was goverment approval on 31 August 2016 for the establishment of seven new free trade zones (FTZs) in China in an effort to combat slowing economic growth.

These included, significantly, Liaoning, plus Chongqing, Zhejiang, Hubei, Henan, Sichuan, Shaanxi, bringing China’s total number of FTZs to 11.

The first clear indicator for magnesite (and talc and graphite) was on 30 October 2016, when Announcement No. 60 of the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) on total export quotas of industrial products in 2017 was published on the MOFCOM website, and for the first time since 1994, magnesia and talc were absent from the listing (phosphate rock and silver remains among the minerals).

However, at the time, apart from this there were no official announcements specific to magnesia and its export administration, prompting almost two months of speculation and concern in the market.

It was not until late December 2016, when MOFCOM officially announced “tax adjustments“ to some of its exported commodities for 2017, effective 1 January 2017, including magnesite (and antimony, tin, indium, graphite, and talc), that it was deemed “official“.

The nature of the final confirmation of such a significant decision, after 23 years of market turmoil, came as somewhat of an anti-climax, with many in the market still grasping the import of it all.

However, there remains some confusion about the need and to whom to apply for export licences required nevertheless, albeit at no cost, for magnesia.

Some observers also have concerns over the threat of a potential “Resource Protection Tax“, which might be implemented by the government for magnesite in an effort to offset the cancellation of export taxes.

CCM shaft kilns smoking away in Haicheng, Liaoning province; a government pollution crackdown has paralysed most calcination plants in the district.

Magnesia plant closures: pollution crackdown

Pollution was stated as the “top enemy” among provincial lawmakers and political advisors at the plenary meetings across China earlier this year.

In Beijing, RMB18.2bn (US$2.6bn.) is to be spent to fight air pollution in 2017, aiming to limit the annual average density of hazardous (Particulate Matter)PM2.5 to around 60 micrograms per cubic meter this year.

This is a country-wide initiative whose ramifications will go further than just affecting magnesia production in Liaoning.

The third Central Inspection Team holding a mobilisation meeting on inspection in Liaoning in early May 2017: the team, stationed in Liaoning for about one month from 25 April, has just completed its tasks, including “a thorough check-up of the local effort in implementing the new development concepts and strengthening the ecological progress and environmental protection.” Courtesy Ministry of Environmental Protection.

On 5 April, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) announced the largest national-level inspection on record. Some 5,600 environmental inspectors were sent to Beijing, Tianjin, and 26 smaller cities in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region – a major hub of mineral processors for export trade – to check on implementation of pollution control targets and emission standards.

They are also to inspect the investigation and closure of polluting businesses, the seasonal reduction or halting of production in certain industries, and the installation and operation of pollution monitoring and control devices.

Liaoning province saw a year-on-year 16.4% decrease in PM2.5 density last year, and 284 days with good air, 26 days more than 2015. Nevertheless, an aggressive provincial government crackdown has seen nearly 6,000 coal-fired boilers dismantled, and over 220,000 high-polluting vehicles phased out.

There is no doubt about the impact of the government’s environmental legislation drive. Since February this year there has been a steady stream of magnesia plants announcing closures and severe cutbacks in production which seemed to have come to a peak in May.

In late February, AsianMetal.com reported that 527 furnaces in 34 magnesia plants were forced to suspend production in Haicheng. In April, 46 plants operating 679 furnaces in Haicheng were closed owing to their not having environmental protection licences.

Workers feeding raw magnesite lumps to shaft kilns at Haicheng, Liaoning; some of the closed furnaces which have been approved to resume production with anti-pollution equipment installed are just starting to come back on line.

One trader commented to IMFORMED that up to 95% of magnesia production (CCM, DBM, FM) in Liaoning has been affected by inspection teams interrupting and stopping production, with few if any high purity DBM furnaces operating.

Another trader explained that cameras are being installed in some plants to monitor dust levels, and should pollution reach a certain level, then the plant is ordered to close its furnaces.

Work to upgrade production facilities with proper equipment meeting environmental standards is expected to take two to three months, although these are reported to mainly concern only dust emissions.

Producers must then conduct trials and apply to the Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau and local government for approval to resume full production. Apparently, all magnesia companies in Yingkou must comply with new environmental standards by 30 September 2017 or face threat of closure.

So it might be from mid-year to end of September before normal operating levels are resumed, if at all for some plants.

Compounding the supply shortage has been increased demand from both domestic and overseas consumers.

Of course, as well cleaning the environment, the pollution controls may well help the Liaoning government solve another of its longstanding issues in the magnesia and refractories manufacturing sector, that of winnowing out the many less efficient plants, and thus overall streamline the industry.

So what can we look out for over the next few months:

- Which operations have been approved to resume production, and to what level of utilisation?

- Which operations remain closed, and which are likely to stay that way?

- Will there be another round of environmental inspections, perhaps to a higher degree, ie. more than dust control?

- Will the upgrading of plants with anti-pollution equipment translate to rising operational costs and thus rising prices?

- How long will it take for resumption of output to catch up with domestic and overseas demand, and then what will happen?

- Prices may firm initially with short supply, then level off: is there another tax on the horizon (Resource Protection Tax?) to offset the export tax demise?

- Should the demise of the export licence system, coupled with a streamlined, environmentally improved, and more efficient supply base in Liaoning stabilise Chinese magnesia availability and prices, what kind of impact will that have on magnesite project developers outside China? ie. one of the main drivers of developing magnesia sources outside China was the unpredictability of raw material supply and prices.

Come to Kraków and find out!

All these issues and more will be under examination and discussion at

MagForum 2017, Radisson Blu Hotel, Kraków, 11-14 June 2017

The only place to be: All you have to know, All you have to meet

Over 170 delegates already registered

Click here for programme | Register Now!

Contact Ismene +44 (0)7905 771 494 | ismene@imformed.com

Why not join the MagForum Community?

Hi Mike,

Very interesting article and I was in Liaoning December 2016 and Yingkou. It was already clear that a lot of small steel plants had to close due to environmental issues. For Europe an increase of recycling, and in other markets like Brazil are a possibility?

Johan