Panglobal action to kickstart domestic mineral projects driven by critical mineral demand

It is regrettable that it takes a pandemic to spotlight what many have been warning about for some years: a shortage of commercially developed critical mineral resources and processing plants, and a risky overreliance on imports from limited overseas sources. But that’s what’s happening.

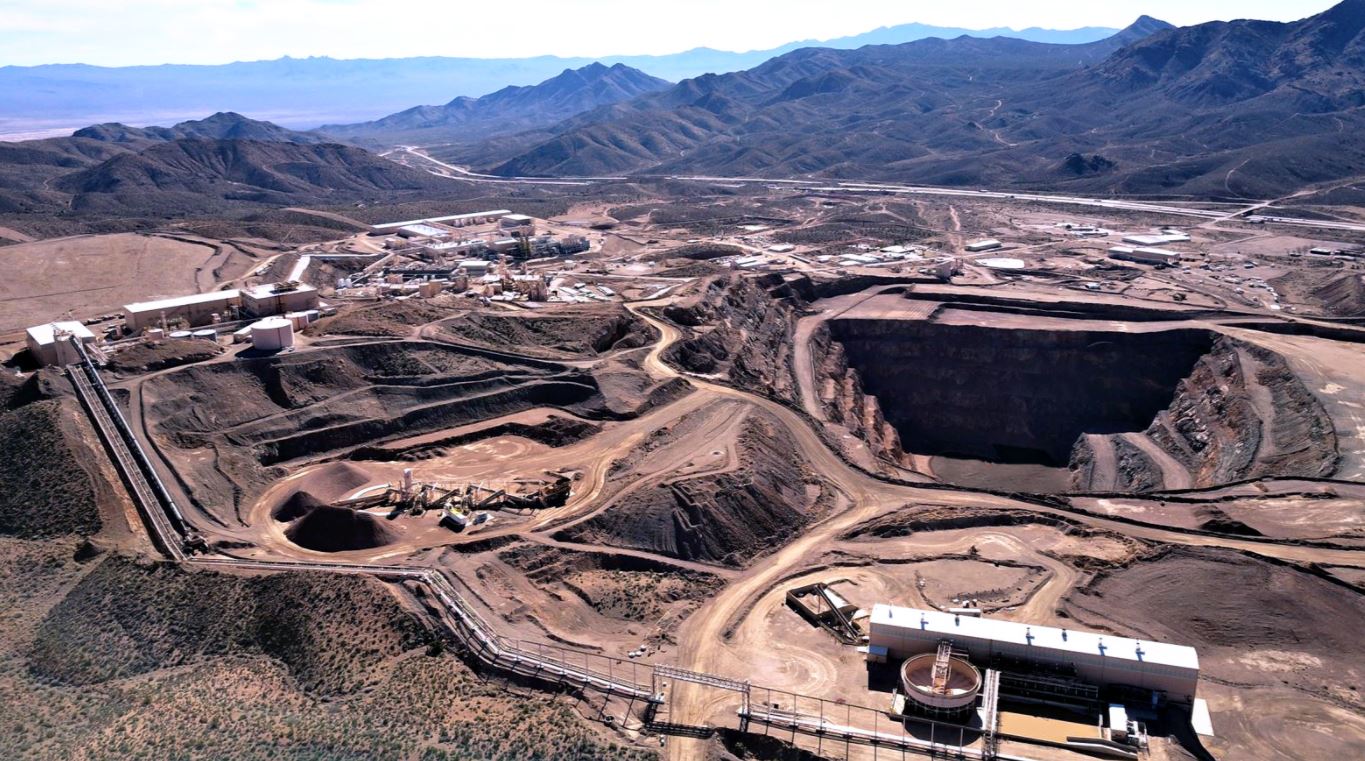

Title picture Mountain Mission: MP Materials, the USA’s sole rare earth minerals producer at Mountain Pass, California, now on a “mission to restore the full rare earth supply chain to the USA”, is expecting to have full processing capacity by 2022, and has recently been issued a contract with the US Dept of Defense. Courtesy MP Materials

Speaking Tuesday last week at the Benchmark Mineral Intelligence Summit 2020, Washington DC – The Keynotes, Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), Chairman, US Senate Committee for Energy & Natural Resources acknowledged that Covid-19 had “helped elevate the issue and given greater recognition of this threat”.

Murkowski made a plea to all concerned to help break down barriers to meaningful legislation and start substantial engagement to source critical minerals domestically before it is too late.

This follows hot on the heels of US President Trump’s Executive Order call to action announced 30 September (see below) and in just the last few days as we near the US Election, US Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has pledged support to boost domestic production of minerals critical to green energy and electric vehicles. The Biden campaign is reported to have privately told US miners that the Democrat will support projects crucial to his climate plan.

And across the Atlantic, earlier on 3 September 2020, as the European Commission announced an invigorated Action Plan, Thierry Breton, EC Commissioner for Internal Market, said: “The pandemic has revealed Europe’s dependencies in certain products, critical materials and value chains”.

For most critical minerals, and also other minerals of significant industrial value which may not be formally labelled as “critical”, it is not that there is a shortage of world resources, merely that for too long consumers have been relying on imports from limited sources overseas while their respective domestic mineral development has received little or no support, thus struggling to bring local/regional mines to fruition.

Sure, initially consistent high volumes, good quality, and above all, low prices, ensured consumers’ attentions and support were very much focused on these imports, while, frankly speaking, in the main, governments were blissfully unaware.

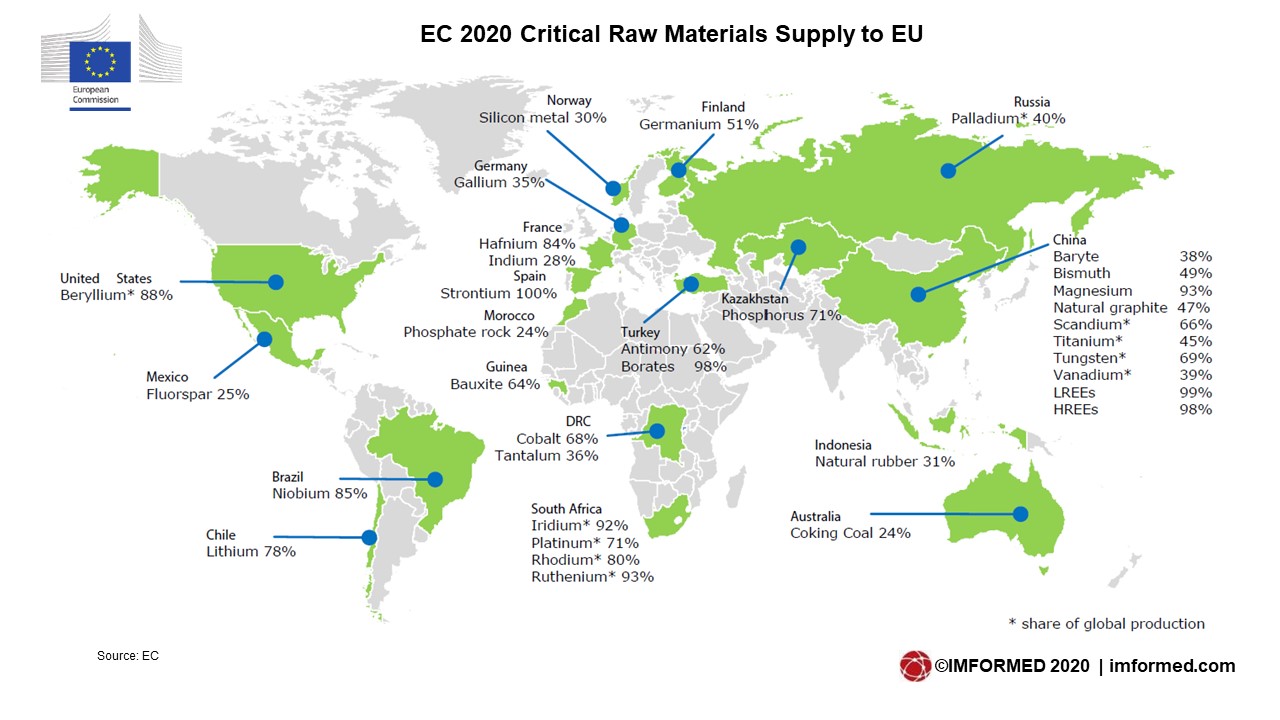

And yes, a large proportion of these mineral sources are to be found in China – mostly down to nature but also down to diligent exploration, development, and hard work on establishing trading relationships by the Chinese mineral sector over the years, initially supported by relatively lower labour, freight, and energy costs, and central and local government incentives.

But times change, other influencing factors are brought to bear and there is now very much a sea change in attitudes, albeit belated to some, in mineral consumer reliance on China and a more enlightened approach in diversification of mineral sourcing strategy.

Find out the latest trends & developments for the industrial minerals market at

The IMFORMED Rendezvous 2021 ONLINE 13-14 April 2021

Full Details

Even before Covid-19 this trend was gathering momentum, driven by two key factors:

1. China in change: the last five years in particular has seen mineral supply from China impacted by inconsistency in volumes, quality, and prices owing to a range of factors including environmental and other central government-imposed controls, exhaustion of high quality reserves, ban on mining and exploration licences, lack of industry investment in modern plant and infrastructure, reduction in production capacity, and a swiftly growing domestic market – in both established and new hi-tech manufacturing – demanding domestic (and more recently, imported) minerals, thus making the export market less a priority for producers. (see China’s refractory minerals crisis: dark days of the Dog continue).

2. Emergence of hi-tech growth markets: particularly in the energy sector (eg. Li-ion batteries, EVs, solar, wind), and especially demand for so-called critical minerals (eg. lithium, graphite, rare earths).

At the beginning of 2020 the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic merely brought into sharp focus the vulnerability of mineral supply chains and the overreliance on China as the primary mineral source.

But it is important to note that this was not just for the emerging hi-tech growth markets but also for established key manufacturing industries such as steel, ceramics, glass, oil and gas drilling (for a review see: China’s mineral supply to global markets: dominance, diversity & disruption).

So what has been the response so far? During the year, and just in the last few weeks, a range of actions and plans have been announced worldwide.

EC revises List of Critical Raw Materials, launches Action Plan

On 3 September 2020 the European Commission (EC) announced an Action Plan on Critical Raw Materials, revised its List of Critical Raw Materials, and published a Foresight Study on Critical Raw materials for Strategic Technologies and Sectors from the 2030 and 2050 Perspectives.

Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President for Interinstitutional Relations and Foresight said: “A secure and sustainable supply of raw materials is a prerequisite for a resilient economy. For e-car batteries and energy storage alone, Europe will for instance need up to 18 times more lithium by 2030 and up to 60 times more by 2050. As our foresight shows, we cannot allow to replace current reliance on fossil fuels with dependency on critical raw materials. This has been magnified by the coronavirus disruptions in our strategic value chains.”

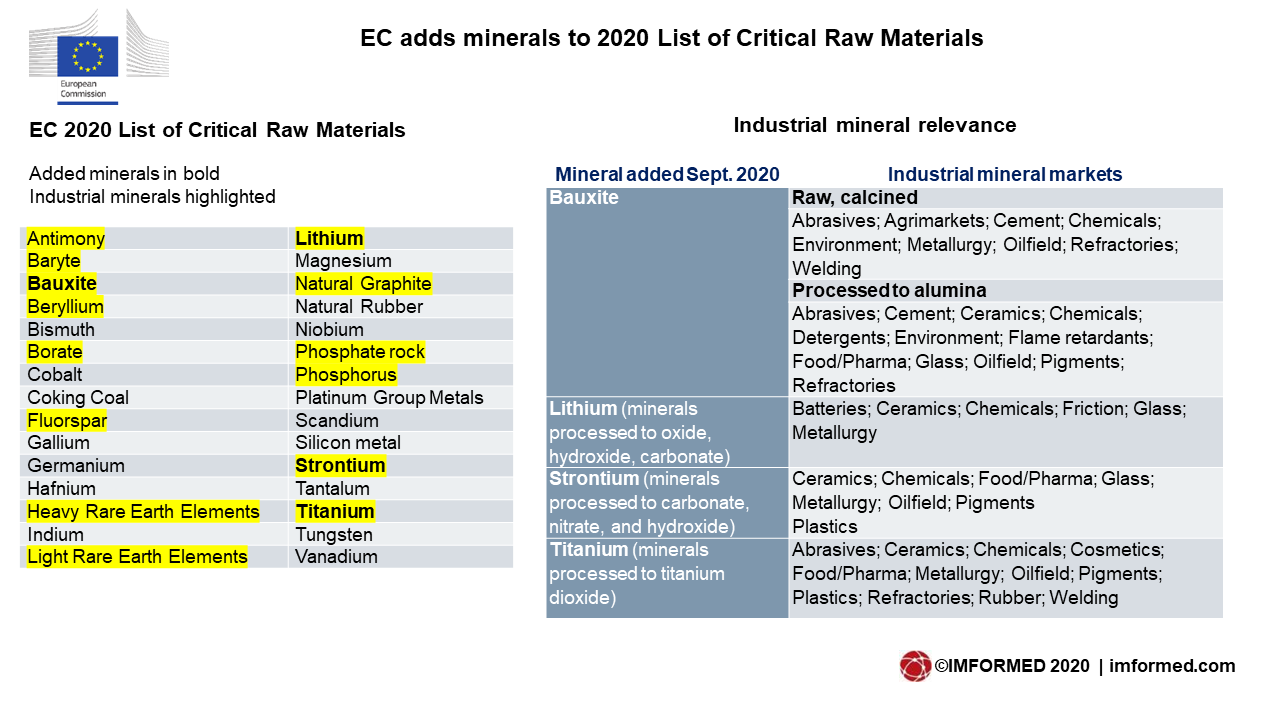

Regarding the List of Critical Raw Materials, last revised in 2017, the EC has now added bauxite, titanium, lithium, and strontium – all key industrial minerals essential to a range of industries, as well as having metallic value (especially bauxite for aluminium).

The EC explained the update “to reflect the changed economic importance and supply challenges based on their industrial application.”

The 2020 EU list now contains 30 materials as compared to 14 materials in 2011, 20 materials in 2014, and 27 materials in 2017. The EC removed helium from the 2020 critical list owing to a decline in its economic importance, and will monitor nickel closely, in view of developments relating to growth in demand for battery raw materials.

Despite the EC assessment of bauxite almost totally focused on its importance in the aluminium metal supply chain, the addition of bauxite is certainly warranted from the viewpoint of bauxite as an industrial mineral.

There are very few sources developed worldwide for non-metallic bauxite grades, and until very recently, China owned and operated all sources of refractory grade bauxite (ie. China and Guyana; see Guyana bauxite newcomer starts bulk shipments).

The EC assessment contains a cursory reference to the non-metallurgical applications of bauxite and bauxite-sourced materials to the downstream manufacturing industry.

No assessment was made for the criticality of the intermediate stage between bauxite and primary aluminium, ie. the production of alumina (which also has many non-metallic markets, see table).

Strontium was assessed for the first time by the EC, and was very much based on its non-metallic market demand. For titanium, both metallic and non-metallic market demand was used in the assessment.

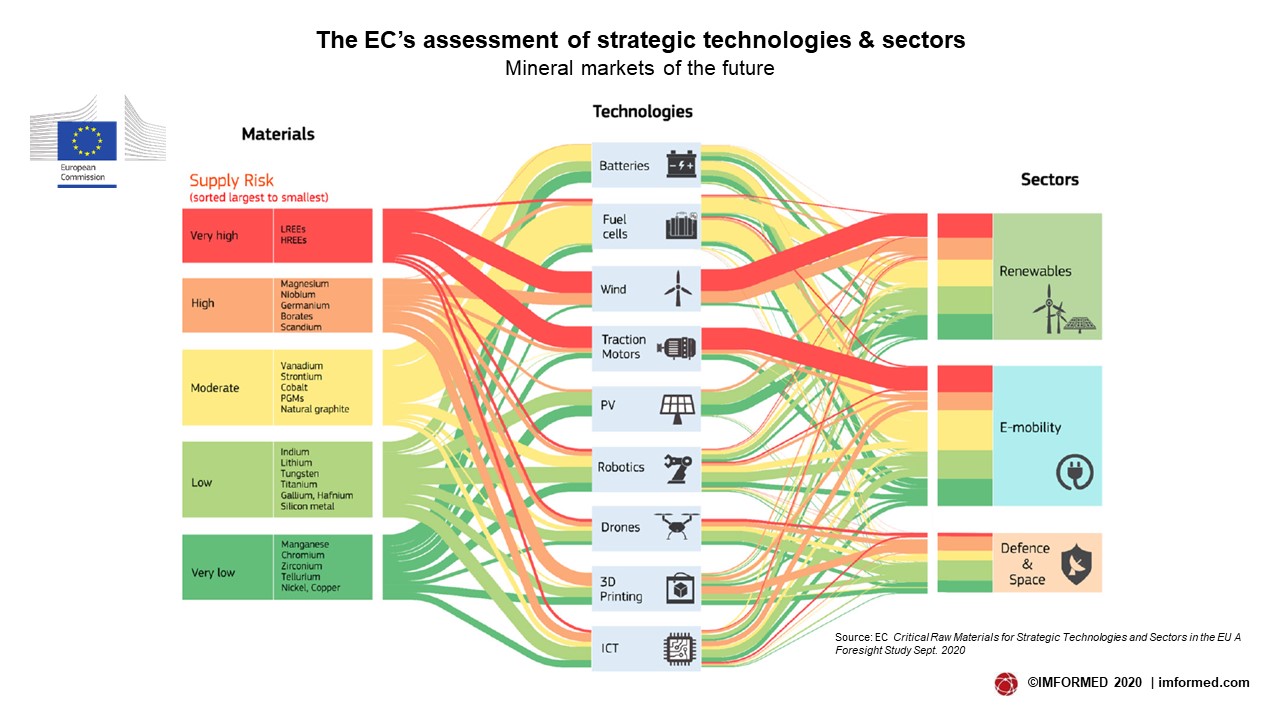

In its Critical Raw Materials for Strategic Technologies and Sectors in the EU A Foresight Study the EC identifies in essence the mineral markets of the future; grouping recognised “strategic technologies” and their respective mineral demands, in the three sectors of Renewables, E-mobility, and Defence & Space.

The EC’s Action Plan, unveiled at the same time, is aimed at reducing Europe’s dependency on third countries, diversifying supply from both primary and secondary sources, and improving resource efficiency and circularity while promoting responsible sourcing worldwide.

The Action Plan comprises ten tasks:

- Launch an industry-driven European Raw Materials Alliance

- Develop sustainable financing criteria for the mining and extractive sectors

- Launch research and innovation on waste processing, advanced materials and substitution of critical raw materials

- Map the potential supply of secondary critical raw materials in Europe and identify viable recovery projects

- Identify priority mining and processing projects for critical raw materials in the EU that can be operational by 2025

- Develop expertise and skills in mining, extraction and processing in regions in transition

- Deploy Earth-observation programs and remote sensing for resource exploration, operations and post-closure environmental management

- Develop research and innovation projects to reduce environmental impacts of raw materials extraction and processing

- Develop strategic international partnerships to secure a diversified supply of sustainable critical raw materials, starting with pilot partnerships with Canada, interested countries in Africa and the EU’s neighbourhood in 2021

- Promote responsible mining practices for critical raw materials

The plan appears detailed, wide ranging, and ticks a number of key boxes, not least a clear emphasis on inclusion of processing projects (so often forgotten while mining is highlighted) and above all, recycling as a key facet of the future: “waste processing”, “supply of secondary critical raw materials”.

However, perhaps what stands out most are the two bold deadlines regarding priority mining and processing projects in the EU that can be operational by 2025, and strategic international partnerships with Canada, Africa and the EU’s neighbourhood in 2021.

Anyone who has been involved in trying to get a new mine started in the Europe will understand just how challenging and arduous the process is of getting it anywhere near to fruition.

But let’s be optimistic. By this Action Plan the EC is clearly laying down a marker that it wants to fast track “priority mining and processing projects for critical raw materials”.

Indeed, since the launch of the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA) on 29 September 2020, over 50 new industrial and non-industrial partners have joined and endorsed ERMA.

The ERMA network now consists of an impressive list of >200 partners from over 30 countries in and out of Europe across the entire raw materials value chain, covering primary raw materials extraction, processing, advanced materials and product design, as well as recycling.

Sweden: a chance for graphite & fluorspar?

Most recently, ERMA has also been supported by the North Sweden European Office, which represents the four northernmost counties of Sweden with a significant share of Europe’s most critical mineral and metals deposits: Norrbotten, Västerbotten, Jämtland Härjedalen and Västernorrland.

North Sweden wants to strengthen its position as a global frontrunner for sustainable development, a reliable and efficient supplier of raw materials, an innovative testbed and a high-tech knowledge hub, as well as a vital facilitator for the European green and digital economy.

One example is the Northvolt gigafactory, partly financed through the European Investment Bank, which will produce lithium-ion batteries for the European automotive industries, while also conducting recycling of critical raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

In June this year, the Swedish Geological Survey decided that Talga Resources’ Vittangi graphite project in Norrbotten county should be designated “a mineral deposit of national interest”.

Talga is planning to build a wholly owned fully integrated anode supply chain in Sweden with development of its anode refinery fed by graphite from Talga’s Vittangi project.

Northern Exposure: Talga Resources’ Vittangi graphite (left) and Tertiary Minerals’ Storuman fluorspar (right)

Under the Swedish Environmental Code, deposits of valuable substances or materials can be defined as being of national interest, meaning municipalities and central government agencies may not authorise activities that might prevent or significantly hinder exploitation of the mineral deposit.

In this climate of renewed interest in critical minerals, it would be surprising if UK mineral developer Tertiary Minerals Plc did not urge the Swedish authorities to take another look at its Storuman Fluorspar Project, in Västerbotten county: a well documented 100,000 tpa acidspar project, granted a mine permit in 2016, and all but ready to go until the permit was rescinded in 2017 in its current form owing to several concerns, since addressed by Tertiary, but remains subject to appeal.

USA: Executive Order from the top

There has been a clamour for development of critical minerals in the USA for some years now, largely led by the rare earths community, but now joined by those realising just how much US new hi-tech growth markets will depend on Chinese and other imports.

But it has only been in the last three years or so that the US government has reacted with any force, and even that has been questioned.

In 2017, there was US Executive Order 13817, a Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure & Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals, followed by the Dept. of Interior (DOI) Final List of Critical Minerals 2018, and Dept. of Commerce (DOC) Calls to Action in 2019.

Also in May 2019, Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), Chairman, US Senate Committee for Energy & Natural Resources launched the American Mineral Security Act, introduced as comprehensive approach to begin reducing the USA’s dependence on foreign minerals.

There followed in 2020 a raft of similarly intentioned legislative announcements, including:

- May 2020: On-shoring Rare Earths (ORE) Act was introduced to end US dependence on China for rare earth elements and other critical minerals used in the manufacture of domestic defence technologies and high-tech products.

- May 2020: American Critical Mineral Exploration and Innovation Act of 2020 aims to reduce America’s dependence on foreign sources of critical minerals by supporting responsible domestic mineral development.

- July 2020: American Mineral Security Act is included in new legislation to help the US recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, ie. the Phase IV COVID-19 relief bill, the HEALS Act (Health, Education, Assistance, Liability Protections, Schools Act).

- Sept. 2020: Reclaiming American Rare Earths (RARE) Act seeks to decrease the US’s dependence on China for rare earths, aims to establish tax incentives for domestic production of rare earths.

And on 30 September 2020, this movement culminated in orders straight from the top: President Trump signed an Executive Order (EO) declaring a National Emergency to expand the domestic mining industry, support mining jobs, alleviate unnecessary permitting delays, and reduce US dependence on minerals imports.

The rhetoric used perhaps underlines the frustration, and may be belated concern over the issue: “I therefore determine that our Nation’s undue reliance on critical minerals, in processed or unprocessed form, from foreign adversaries constitutes an unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.”

“Many Americans are not understanding the fundamentals of minerals, and oppose all mining. The challenge now is to modernise our policies at federal levels so that we can produce more minerals.” urged Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) during the Benchmark Minerals webinar last week.

The aim is that the EO begins the process for the DOI to develop a programme to use its authorities under the Defense Production Act (DPA) to fund mineral processing that protects national security.

Key to prospects for US mineral development, the intention is that this action will accelerate the reopening and expansion of US mines and processing plants.

Critical minerals from China were spotlighted: “The President will continue to protect our domestic supply chains for critical minerals from predatory Chinese action.”

The EO pronouncement highlighted other critical industrial minerals (as determined by the US DOI) and their key markets such as barite and graphite.

Also of interest, was the prospect of widening the scope of mineral development beyond the so-called critical minerals: “In addition, I

The DOI has until the end of the year to report back to the President with its conclusions from the investigation and recommendations for executive action, which could include the imposition of tariffs or quotas, or other restrictions on import source countries. Thereafter, a report is expected every 180 days on the latest on the threat to US mineral supply chains.

Just on a final note re. the US: as has been well documented elsewhere, during 2018-19 the US imposed tariffs on a wide range of >$550bn worth of Chinese imports including certain industrial minerals and mineral products.

One interesting offshoot of the situation that became apparent earlier this year was highlighted by leading Chinese refractory producer Puyang Refractories Group Co. (PRCO) announcing plans to construct a new magnesia-carbon brick plant in Kentucky (see Magnesia from the “Roof of the World” to Kentucky).

While US import tariffs have been imposed on Chinese magnesia-carbon bricks, one of PRCO’s main products, imports of the product’s main raw material, refractory grade magnesia (in this case high purity dead burned magnesia from Tibet) have been excluded from the tariff list, mainly owed to US refractory industry lobbying.

Thus through its US subsidiary, PRCO will be able to supply the recovering US refractories market with a new 22,000 tpa brick plant in Hickory, KY using imported refractory grade magnesia.

Whether this encourages other Chinese manufacturers consuming minerals to set up plants overseas and import Chinese feedstock raw materials remains to be seen.

Elsewhere: Canada | Brazil | Australia | India

Canada-US joint action

On 9 January 2020, Canada and the US finalised the Canada–U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration.

The Action Plan will guide co-operation in areas such as industry engagement; efforts to secure critical mineral supply chains for strategic industries and defence; improving information sharing on mineral resources and potential; promote joint initiatives, including research and development cooperation, supply chain modelling and increased support for industry.

Brazil’s Mining Development Programme

On 29 September 2020, a very wide ranging and comprehensive Mining and Development Programme (PMD) was launched by Brazil’s Ministry of Mining & Energy (MME).

The MME has been working on this since 2019, and it comprises 110 well-defined goals, in addition to actions in ten thematic concentration areas for mining for the period from 2020 to 2023.

The overall objective is to promote the growth of the entire Brazilian mineral sector, and includes the project “Mining of the present for the future”. This entails among other tasks, defining the policy for minerals of strategic interest for Brazil, and taking steps to strengthen their supply chains.

Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy

In March 2019, Australia launched its Critical Minerals Strategy, aimed to position Australia as a leading global supplier of “minerals that will underpin the industries of the future”. This includes the agritech, aerospace, defence, renewable energy and telecommunications industries.

This was followed in November with the formalisation of an Australia-US partnership on critical minerals focused on developing both nations’ critical mineral assets; a project agreement was signed by Geoscience Australia and the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

In January 2020, the Australia government opened the Critical Minerals Facilitation Office to provide national policy and strategic advice on critical minerals, and connect Australian critical minerals projects to investors, regulators, government financing facilities and Australia’s strategic partners.

On 21 October 2020, the government released an updated edition of the Australian Critical Minerals Prospectus 2020 for investors to identify the commercial opportunities within the country’s mineral projects. The prospectus aims at attracting more investment towards critical minerals projects and greenfield opportunities in Australia.

Over 200 potential investments are outlined in the prospectus for critical minerals including lithium, cobalt, manganese, antimony, tantalum, zirconium, tungsten, vanadium and niobium.

India: Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan | Steel & refractories lead domestic utilisation drive

On 12 May 2020, in response to the pandemic’s disruption of the country’s economy, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced an overall economic assistance package worth US$260bn, 10% of India’s GDP.

The stimulus package came with a key emphasis of Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan – self-reliant India – the pursuit of policies that are efficient, competitive and resilient, and being self-sustaining and self-generating.

Although India is endowed with many industrial mineral resources, its refractories sector (supplying the rapidly expanding steel, cement, glass industries) has relied heavily on imports of both refractory raw materials (eg. fused and dead burned magnesia, bauxite, mullite, fused alumina, graphite, silicon carbide) and refractory end products, eg. mag-carbon bricks, and mainly from China.

India’s steel industry requires some 1.2m tpa of refractories, of which almost 30% is imported. With several major infrastructure projects in the pipeline, in his presentation at last year’s Indian Minerals & Markets Forum 2019, Sameer Nagpal, CEO, Dalmia-OCL, expected steel refractories demand in India to double from 1.4m tonnes in FY20-21 to 2.8m tonnes in FY30-31, and cement refractories demand to increase from 0.28m tonnes in FY18 to 0.42m tonnes in FY31 (see India’s mineral markets potential dances to the Bollywood Beat)

First stirrings of a recognition of this supply dependency on imports were apparent at IREFCON 2018 (see Refractory raw material supply “the single most important challenge” )

In FY17, India’s imports of refractory materials surged 40% from Rs180m in 2016 to Rs25.3bn; and in FY 2018 increased by 49% year-on-year to Rs37.6bn. Overall, India’s refractory sector imports about 40% of its raw material requirement from China.

In common with refractory markets elsewhere in the world, India’s refractory manufacturers experienced disruption in raw material and refractories supply as the pandemic hit China early 2020, a sharp reminder of their supply chain vulnerability.

In July 2020, JSW Steel Ltd, India’s second largest private sector steel company, announced that it would cease all imports of materials from China. JSW Group chairman Sajjan Jindal said: “We have recently put a clause in all our purchase orders that specifies no materials should come from China. At JSW, we used to import around 100% of refractories from China, and now we have worked out an alternative supply from Brazil and Turkey, and some from India.”

Dalmia-OCL is India’s fastest growing and second largest refractories group and has been instrumental in leading the call for more utilisation of domestic resources and manufacturing.

In September 2020 the company started up the first phase of its 108,000 tpa mag-carbon refractory brick plant at Rajgangpur, Odisha, comprising of three phases of 36,000 tpa each. When up to full capacity the new plant will be India’s largest mag-carbon brick plant, taking a 25% share of the market, and, crucially, will substitute some 50% of India’s imported mag-carbon brick requirement.

Dalmia-OCL CEO Sameer Nagpal has proposed a plan to encourage the Indian refractory industry to be self-sufficient, while the start-up of its new mag-carbon refractory brick plant at Rajgangpur, Odisha is expected to substitute some 50% of India’s imported mag-carbon brick requirement. Courtesy Dalmia-OCL.

Dalmia-OCL CEO Sameer Nagpal has proposed a three-pronged approach to encourage the Indian refractory industry to effectively contribute to the dream of a self-reliant India:

- Unlocking access to local sources of raw material

- Collaboration between refractory makers and users

- Special benefits and incentives from the government to catalyse the speed with which refractory makers can scale up to meet the demands of Atmanirbharbharat and to ensure ample availability of locally made refractories for steelmakers as they move towards their long-term steel production goal of 300m tpa

India’s ambitious steel growth plans (India now ranks world no.2 steel producer after China, overtaking Japan in 2018) has already attracted much foreign investment from leading refractory players in recent years, such as Krosaki-Harima, RHI Magnesita, Imerys/Calderys, Seven Refractories.

Now these players are further strengthening their raw material, intermediate, and end product supply to India’s refractories industry, including raw material sourcing from outside China.

Mineral sourcing strategy rethink: 2020 examples

The year has already seen a number of interesting announcements regarding changing and innovative strategies in mineral sourcing and processing of critical minerals. Many of these tick the boxes of sourcing security and diversification, consumer vertical integration, and market diversification.

Graphite

Elkem ASA, Norway : Si & C producer diversifying; Northern Recharge Project, Herøya, potential large-scale plant for battery graphite production. Elkem constructing US$7.2m pilot plant in Kristiansand, expected to open early 2021.

Imerys, Switzerland: to invest €35m at its plant in Bodio, Switzerland, to expand the production of high-purity graphite materials in order to supply growing demand from battery manufacturers in Asia, Europe and North-America, who are rapidly increasing their output.

Lithium

Rio Tinto, Serbia, USA: Rio Tinto has approved an additional investment of almost $200m to progress the next stage of the development of the lithium-borate Jadar project in Serbia. Also started work on the commissioning lithium “demonstration plant” extracting lithium from waste rock at Boron, CA mine.

Sibelco, Zimbabwe: Sibelco signed offtake agreement to buy 100,000 tpa ultra-low iron petalite over seven years from Australian developer Prospect Resources’ Arcadia lithium project in Zimbabwe.

Tesla, Nevada: Tesla is to build a lithium hydroxide chemical plant in Texas in what is the first move by an automotive company into lithium chemical production. The plant will be adjacent to the Terafactory/Gigafactory 5 in Austin, Texas. Hard rock spodumene ore will be converted into lithium hydroxide for direct use in its battery cells – a process that traditionally occurs in China using Australia-sourced spodumene.

Fluorspar

Commerce Resources, Canada: has announced plans for its advanced-stage Ashram rare earth deposit in northern Quebéc to upgrade the mine’s potential fluorspar by-product.

Ares Strategic Mining, USA: high grade assays bolster development of Lost Sheep Fluorspar Project, Utah with potential to be only mine in USA; secured two-year 60,000 tpa metspar offtake agreement with Possehl Erzkontor North America; strategic partnership with the Mujim Group, a Shanghai-based fluorspar producer and trader.

Magnesia

Refratechnik, China, Australia: German refractory major invested in 100,000 tpa magnesia processing JV Haicheng, Liaoning, China; and in 2020 acquired (from Sibelco) major magnesia producer QMAG, Australia (>300k tpa); primarily for DBM/FM, but also looking at CCM non-refractory markets.

Rare earths

MP Materials, USA: MP Materials, the USA’s sole REE producer at Mountain Pass, merged with private equity firm Fortress Value Acquisition Corp., in a “mission to restore the full rare earth supply chain to the USA.” In July, the US Dept of Defense issued a contract with MP Materials, which is expecting to have full processing capacity by 2022.

Mineral recycling evolution to accelerate

And finally, these developments in mineral sourcing strategy will also be accompanied by the continuing evolution of the mineral recycling sector.

This is expected to accelerate, driven by benefits of alternative recycled mineral sources, cutting costs (from waste disposal), the overall move to develop the Circular Economy to protect the environment, and to provide mineral suppliers and mineral consumers with a “green” portfolio.

Find out all the latest developments in mineral recycling at IMFORMED’s

Mineral Recycling Forum 2021 ONLINE

12.00-17.00 GMT Tuesday 9 February 2021

Full Details

It is significant that the EC’s recently announced Action Plan, in line with the “European Green Deal”, will also address circularity and sustainability of the raw materials value chain, develop sustainable financing criteria for mining and extractive sectors by the end of 2021, and map the potential of secondary critical raw materials from EU stocks and wastes to identify viable recovery projects by 2022.

The future should see:

- Opportunities to process minerals from waste, develop & supply sorting technology & equipment

- Increasing economic alliances between waste sources (end users) + recyclers, new logistic chains

- Supply chain co-operation in modifying end product formulations to ease end-of-life recyclability

Another expected trend will be more primary mineral producers involved in recycling tailings and other waste sources to offer wider product range (including blends?). Projects announced this year include:

LKAB, Sweden: REE, fluorspar, gypsum, phosphorus from iron ore tailings

Hindalco, India: to supply 1.2m tpa bauxite residue to UltraTech Cement

Noranda Alumina, USA: to supply 60k tpa bauxite residue to CemTech Materials

Rio Tinto, Canada: scandium oxide from ilmenite processing waste

Nutrien/Arkema, USA Nutrien: to supply 40k tpa anhydrous HF from phosphate rock processing FSA waste to Arkema (replacing fluorspar imports)

Future fluorspar alternative? Nutrien’s huge Aurora, NC phosphate mine (1) produced 4.3m tonnes phosrock in 2019, supplying its processing complex (2) (prod. cap. 5.4m tpa phos. concentrate, 1.2m tpa phos acid, and 0.8m tpa DAP/MAP). By 2022 a new 40,000 tpa FSA-to-AHF plant will be installed (may look like 3 – this is FSA-to-AHF plant built by Buss ChemTech in China) to supply Arkema’s Calvert City, KY plant (4), producing fluoropolymers and fluorochemicals (5).

With such projects in progress, changes in mineral sourcing strategy, and a boost from national and regional initiatives and legislation, the 2020s will certainly herald a new era of industrial mineral and mine developments. This cannot come soon enough in order to stimulate economies and meet demand when market recovery starts in earnest.

IMFORMED looks forward to covering all these developments in next year’s exciting agenda of Forums – latest details here.

Interested in presenting?

Please contact Mike O’Driscoll mike@imformed.com | T: +44 (0) 7983 986 255

Interested in sponsoring/exhibiting?

Please contact Ismene Clarke ismene@imformed.com | +44 (0)7905 771 494

dear Mike,

First of all, I hope you and your family & friends are doing well, in these Covid-19 era.

Great, high quality article 🙂

I wonder if there will be any new serious mines be opened in Europe the coming decades. I have followed the Storuman Project as from day one and it tells the story quite clear. Times change, I know, but I assume there will be also lack of investors as they turn to other. more saver investments these days (gold mines ?).

Same problem is in the EV batteries production, impressive numbers of tobe built megafactories, also in Europe (Northvolt) but where to get the suitable raw materials in the required volumes ??

So, challenging times, for all people & companies active or strongly related to this global, industrial mineral industry.

Hi Robert, and many thanks kind words and comment; yes, I feel and understand your “reality check”, which also chimes with other’s comments re. say Sweden’s CM prospects along lines of “they want the critical minerals, but not the mining”! But I do wonder now, and given the EC Action Plan’s bold deadlines and other country’s high profile stimulae, whether we have come to a decisive moment on all this. Let’s see, and stay well.